For as long as most of us can remember, the matter of the absentee father has been so much a part of our social structure that it seems the phenomenon has been normalised. One medical doctor calls it “a social and public health emergency” (Bonas, 2014).

More than a third of our nation’s children have no father figure and over 90% of households have the parenting role being performed by the birth mother or a grandmother (PIOJ & STATIN, 2014). The negative impact is seen and felt not only within the immediate family context in the form of limited financial resources and frequent child neglect, but extends into the adult years, predominantly in the form of impaired socio-emotional development which can manifest as increased risky behaviour and academic underachievement (McLanahan, Tach, & Schneider, 2013).

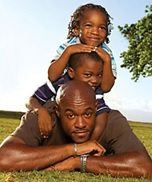

Opposite outcomes have been found in the case of the involved father with favourable effects also extending to the mother, resulting in better physical and mental well-being (Allen & Daley, 2007). Note, however, that positive effects are associated with the involved father, not just a father who is physically present. The involved father may be described as one who plays an active role in the life of his child, providing support in his/her social, emotional, physical, cognitive and spiritual development.

So do these fathers exist in Jamaica and just what does it take for our fathers to be involved in the development of their children? These are some of the questions a local researcher sought to answer in her study: An investigation of fathers’ involvement in the holistic development of their children in rural Jamaica (Jemison, 2015). To probe the issue, Jemison conducted interviews with and observed fifteen (15) fathers from eastern and western sections of Portland who were evidently involved in the upbringing of their children at the early childhood level (ages 3-5).

How involved are fathers in the holistic development of their children?

Most fathers spoke to being actively involved in many different ways, undertaking responsibilities such as: school pick-up/drop off; assisting with school work; participating in PTA; cooking; doing laundry; playing games; taking children to church; and taking children to the hairdresser’s or combing the hair themselves. Noteworthy is that several fathers believed that good parenting was more than providing for their children’s basic needs and necessarily includes nurturing the bond between father and child.

What are the factors affecting fathers’ involvement in the holistic development of their children?

The most common challenge given by fathers was unemployment with 40% stating that much of their energy had to be directed towards ensuring food is on the table and school fees are paid. Other common factors included: the need for maternal support (20%); separation from children (10%); work interference (10%); role as punisher rather than disciplinarian (10%); and lack of awareness of various means of engaging with children, such as reading (10%). What is important is that rather than being opposed to the idea of actively engaging in their children’s upbringing, most fathers desired to be involved but often found that the challenges interfered with this desire.

How do fathers respond to parent education programmes and support for their involvement in their children’s holistic development?

After participating in a 12-week parenting programme, fathers provided feedback on their experience. All responded positively to the programme stating that it helped to enhance their abilities as fathers. Additionally, several participants expressed tremendous gratitude for the recognition that was afforded them, as fathers, through the programme. Comments hinted at the once prominent issue of the marginalised male remaining a lived reality among many Jamaican men.

The findings of Jemison’s study suggest that while there do exist fathers in Jamaica who are actively involved in their children’s development, multi-faceted support in raising their offspring is both welcomed and necessary. Hopefully, this project will inspire greater investment in similar programmes, enabling the vision of positively impacting greater numbers of men and fathers to be realised.

– To learn more about this study email the researcher, Pauline Jemison, at jemisonpauline@yahoo.com

__________________

Bonas, S. (2014). Absence of fathers in homes described as social emergency. The Gleaner. Retrieved from http://www.jamaicaobserver.com/news/Absence-of-fathers-in-homes-described-as-social-emergency_16803482

Planning Institute of Jamaica (PIOJ) and STATIN (2014). Jamaica survey of living conditions 2012. Kingston: PIOJ and STATIN.

McLanahan, S., Tach, L., & Schneider, D. (2013). The causal effects of father absence. The Annual Review of Sociology, 399-427.

Allen, S. & Daley, K. (2007). The effects of father involvement: An updated research summary of the evidence. Guelph: Centre for Families, Work & Well-being. Retrieved from http://www.fira.ca/cms/documents/29/Effects_of_Father_Involvement.pdf

Jemison, P. (2015). An investigation of fathers’ involvement in the holistic development of their children in rural Jamaica (Unpublished master’s dissertation). University of the West Indies, Mona, Jamaica.